As someone who loves travel, I love freedom of movement. And yet I love boundaries too. Boundaries are a miraculous and very fundamental part of life on planet Earth. Nature is rife with them, be they cell walls, river banks, or animal skin. Without boundaries we’d all be floundering in a beige soup of indistinction. There would be no identity. No autonomy. And...contrary to what we often believe, little harmony either.

Even so, I still love freedom of movement, and it’s a beautiful contradiction to explore.

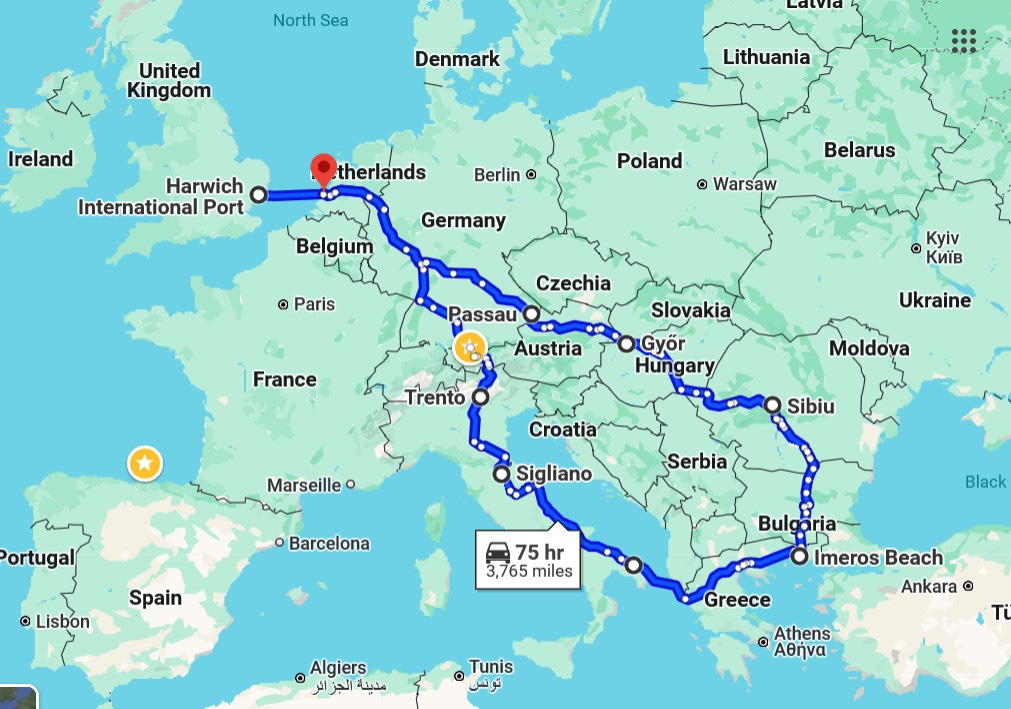

These past seven weeks during my lengthy voyage through Europa, I’ve been crossing borders and boundaries of all kinds. Some of them hard borders, some of them soft, some of them natural borders like rivers or mountain ranges, some of them human-made. Sometimes passports were checked, sometimes they weren’t. Sometimes I didn’t even realise I’d crossed a boundary until I noticed a change in language or time zone.

And do you know what? I’ve fallen in love with this mottled continent in the process. Because with each crossed border, I’ve marvelled that this extent of variety in language, landscape, food, and culture could possibly coexist in such a small space. Sometimes I traversed an entire country in less than two hours, and in that short time everything from the cheese to “good morning” had changed.

A Motley Union

My latest drive adventure has taken me through eight countries, and with the exception of Germany and Austria, each land spoke a different language (sometimes multiple languages). Sometimes the countries in question were completely linguistically alien from each other. Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria speak tongues that are etymologically almost unrelated. Nevertheless, these nations all had one thing in common: they were part of the European Union. And no matter what you think about that, you have to admire the attempt to gather such a disparate horde around a negotiating table at all. It’s the triumph of optimism over centuries of murderous acrimony.

Yet, how diverse and distinct these (mostly little) lands are! Punctuality, food, speed limits, coffee — it’s all up for debate. While driving through the spacious forested countryside of Germany, I found I was forever late. Most guest houses and hotels closed their check-in at 6 pm (yes, really) and I was chided more than once for not making that cut off time. I began to think they’d deport me for being just too irregular and tardy. Austria was much the same, with me tensely pressing the gas as I hurtled passed the staring cows. Yet as soon as I slipped over the border into Hungary or Italy, I could cruise as laggardly as I pleased, while gazing at the sunset in my rear-view.

It was a similar state of affairs at the breakfast table. In Greece breakfast finished at a leisurely 11 am (yee-ha!) whereas in Austria it was 9 am at the very latest. Then there was the smoking: In Bulgaria a miasma of cigarette smoke seemed to hang like nimbostratus in the upper corners of most restaurants. In Greece, the smokers were slightly less brazen, puffing next to an open window when no one was looking. Yet as I headed westward, the fog gradually thinned to a fine mist, until I reached the Netherlands where these types of shenanigans are well and truly illegal.

Speed limits were another moving target. In Germany there was no speed limit on the Autobahn (yup, you can drive as fast as your BMW can zoom — and let me tell you, that’s pretty excitingly speedy). Over in Romania on the other hand, for reasons I’m yet to unearth, the tendency seemed to be for mooching along at a excrutiating 50 km per hour. In Italy it was another game altogether, with the signs clearly showing 70 km per hour but most seeming to drive at 100 km per hour regardless.

And finally there was the coffee. Oh the coffee! The Netherlands and Germany both still produce solid old school filter coffee, while over in Hungary and Greece the dreaded Nescafe lurked here and there. In Romania, tea was the way to go, with the country producing some of the best herbal varieties out, while over the river in Bulgaria I found a secret and unexpected coffee Mecca. You could even buy a decent Americano from vending machines in tiny mountain villages. Finally there was Italy. He he he. And here my friends it was espresso or die. “This is Italee! We don’t serve Americano, because iss ‘orrible!” said one cafe owner to me in Apuglia, before slamming an espresso in front of me.

I loved it all — the continually shifting rules, the perfectionism about the food, the musical intonation of the languages (and the joy of learning them), the jibing, the local shops, and the glorious lush beauty of Europe. It made me feel anything was possible in this world.

Schengen

Nevertheless, I’m still awed that somehow, some way, on one sunny day in Schengen on the 14th June 1985, this motley rabble of nations gathered in a single room — along with a couple of thousand interpreters — and forged the most ambitious freedom of movement agreement in modern history*. Even just imagining the coffee machines is enough to give me a headache. Or did they hire specially trained baristas, whipping up a cafe con leche in one hand and a pot of Darjeeling (with a jug of cold milk if you please) in the other?

I was fourteen years old when Schengen was first signed. I am the freedom of movement generation. By the early 1990s, it would come into full force, allowing borderless travel between many European states. I remember it well. That agreement allowed me to work in a Bavarian Kur hotel, spend a year as a stagiaire in Paris, and study in Leipzig too. It opened my mind, and a whole field of opportunity for me.

So yes, I love freedom of movement. And yet I love boundaries too. To deny boundaries is to deny reality. But my, they do seem to cause a lot of strife, don’t they? Or do they?

The Paradox of Natural Boundaries

When two different substances, beings, or cultures meet, there will inevitably be an edge. There has to be in order for one entity to be distinct from another. Cells have membranes, each human and animal possesses skin, plants have bark or an epidermis. Groups of entities also create boundaries (the human body is a group of cells with an epidermal boundary, a lake is an entire ecosystem with the water’s edge as the border).

When you live in the heart of nature for a long time, you become quite familiar with nature’s boundaries. Animals define their territories very clearly both vocally and with scent, and anyone who is nature savvy knows to take those borders seriously. I became like an animal when living off-grid in the wild, and I remember the magical power of walking my land perimeter, how I could sense everything, from the ants to the wolves, was watching and listening to me.

As a natural builder, I have my own take on what creates a healthy wall too, and I duly bark on about it over at The Mud Home. House walls need to enable air and vapour transfer, otherwise they don’t allow evaporation and end up suffocating the building causing rot, smells, mold and other nasties. Nature agrees with me.

The curious thing about all of nature’s boundaries is that they are neither fixed nor impermeable. They have a dual purpose: On the one hand, they protect and contain entities, yet on the other they are crossing points for information, life, air, food, water, assistance, and technology. Lose either of those aspects and the integrity and survival of the cell or entity is compromised. So the great paradox with boundaries is this: For a healthy organism, a boundary has to be both clearly defined and protective, yet also permeable and able to shrink or grow. If we began with this curious natural paradox as a starting point, we might get a whole lot further in solving our own human issues with boundaries.

When Did Country Borders First Arise?

When I began researching the first human-made land borders, the results were vague. The concept of state borders has evolved gradually over thousands of years, with the Great Wall of China being one of the earliest human-made political boundaries. For the Romans, borders were more administrative than anything (European bureaucracy staying true to form even two thousand years ago, sigh).

Borders as we understand them today, however, really are quite a recent invention. They arguably start with the treaty of Westphalia, a long, drawn-out peace accord that finally came about after almost a hundred years of bloody war in Europe, and eight million deaths. That treaty was an utter revolution in terms of international contracts, and is the precursor for most peace accords today. If you want to see the staggering complexity of central European borders in 1648, do take a look. That they even managed to scribe this on paper is pretty incredible.

What transpired as a result of the Westphalia Peace Treaty is that we learned a few things, namely that commonly agreed boundaries significantly improve the chances for things like: diplomacy, justice, and democratic sovereignty, as well as enabling clear jurisdiction and trade agreements. They help prevent conflicts between nations, and provide a framework for negotiation and cooperation. They don’t always work. Nothing always works. That doesn’t mean it’s not an improvement on what went before, namely sitting in your village waiting for the next murderous band of thugs to roll up and decimate or enslave you. Thus, despite all that’s happened since in Europe, I’ll still give a nod to those delegations of diplomats in Munster and Osnabruck who battled on and on to forge that peace agreement. It wasn’t perfect (show me something that is), but it was brave, and a real step in the right direction.

Today many hate the E.U. or U.N. or any other of these (admittedly flabby, creaky and at least partially corrupt) organisations. Certainly, I too have my misgivings. But that doesn’t render the underlying attempt to create a framework for negotiation and accord any less worthy. What we need is for these structures to evolve into something more organic, democratic, and fair. What we don’t need is a bunch of bombastic nitwits dragging us back to the 1600s. Because the important aspect of an agreement is that it’s negotiable, (unlike war, which isn’t). Agreements aim to be win-win. War is always lose-lose (unless you own shares in the arms industry of course).

Back on the Road

But back to the road. This week, I finally put almost 4000 miles of road behind me, reaching the Hook of Holland once more. The wind whipped the water into volatile peaks, while the Dutch ferry’s mouth gaped open before me, a steel whale imbibing me and my car whole. As I rolled onto the gangplank, I hugged my steering wheel like an old friend. My Dacia and I have been many places these past weeks, and we are both somewhat transformed from the cold day in May when we began this voyage.

As I reclined with a cappuccino in the ferry cafe and closed my eyes, a party of memories crowded onto the decks of my mind, turning my inner world into a festival of wonderment. I saw the azure clarity of the Greek coves that I’d snorkelled in, and the unparalleled taste of real feta cheese as I kicked back in tavernas for dinner. I recalled driving up to the incredible rock top monasteries of Meteora with a Brazilan woman I’d met in a hostel. After that, my mind’s eye turned to the stork nests in Bulgaria - huge twiggy bonnets perched on electric pylons complete with fluffy, white baby stork’s heads popping out of them. I remembered the delicious smoothness of the Bulgarian sour cream and the surprising lushness of the mountains. Soon, the stone trullis of Apuglia shuffled into view, and I recalled the warm dusky air on my skin while wandering through the hobbitland of Alberobello. Next the Dolomites rose before me, towering rocky gates to the mythical world of the Alps. And the road? Ah the road…it wound through them and over them, into Austria, Germany and beyond. As I drove along it, it was like riding on the back of a continental black dragon, snaking endlessly through Middle Europe.

I’ve crossed many boundaries these past seven weeks, both internally and externally. Sometimes people have tried to cross mine too, now I come to think of it. But with all this difference and variety, colour and uniqueness, we must honour our edges, and yet simultaneously, be forever prepared to renegotiate them. Because the world isn’t standing still. Whether we resist or not, other ideas and points of view will reach us every single minute, upon which we automatically redefine who we are. Nothing on this planet is fixed, and everything is always on the move, developing and growing, or receding and shrinking. This is the organic, ever-shifting mosaic that is life on Earth.

It was evening when the suprisingly blue shores of England drew into view. The iron necks of the cranes were raised, as if stretching up to see who was arriving. Soon, our hulking ship spat my car out into the port of Harwich. Driving duly up to the UK border, I wound down my window and handed my passport to the official in the box. He scanned it, looked me up and down, and then smiled.

“Been anywhere nice?” He said.

I took a breath and paused. What in Europa was I supposed to say?

*In fact only 5 countries signed on that date: France, Netherlands, West Germany, Luxembourg and Belgium. Freedom of movement wasn’t properly implemented until the Schengen convention in 1995 when many more member states were included.

I’m sharing the vlogs of my voyage with paid subscribers and all those supporting my work on Patreon.

I remember bringing up Schengen in the great Brexit debate that rumbled long after 2016. So few Brits realised that after entry into a Schengen state, another visa was needed into UK for non EU citizens

I guess boundaries are as old as the earth itself. But taking the Schengen Agreement into account I love it! Crossing those other borders can be bloody intimidating.

Fabulous writing as always!